Minnesota’s Early Farmers

From Ancient Days to 1900

Native Americans

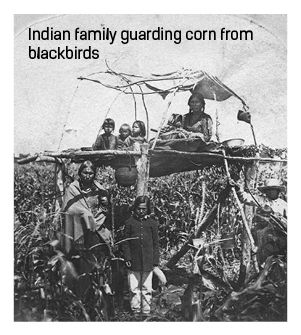

Long before immigrants arrived and Minnesota became a state, the Ojibwe (sometimes called Anishinaabe) and the Dakota Native Americans farmed. The Ojibwe lived in the northern lakes and forests. They hunted and fished. They harvested wild berries, other plants, and wild rice. The Dakota settled in the prairie areas in southern Minnesota. Their villages dotted the Mississippi, Minnesota, St. Croix, and Cannon River banks. Dakota men were hunters and warriors; Dakota women were farmers. They grew corn, beans, and squash, a crop trio called the Three Sisters in native lore.

Today, Native Americans honor their agricultural heritage by growing and harvesting traditional crops like hominy (a type of white corn), wild rice, wild berries, maple syrup, buffalo meat products, and use birchbark to make baskets and crafts.

Early Immigrants

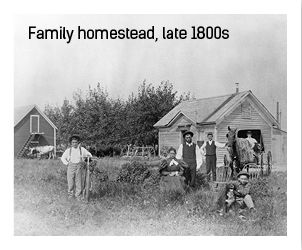

Immigrants from Europe began arriving in the early 1800s. They settled on small plots of land and were subsistence farmers. They grew just enough food to feed themselves and their farm animals, with some left over to trade for things they needed. It was a hard life, with little money, meager tools, crude homes, and few household goods. Subsistence farmers raised a variety of crops and livestock. Farms that grow a variety of crops are called diversified farms. Many farmers at that time planted oats, potatoes, corn, and beans. They kept a cow or two, a few chickens and pigs, and maybe a few sheep.

Free Land ... Westward Rush

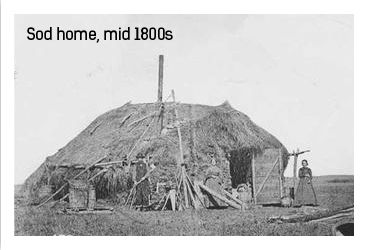

The Homestead Act of 1862 provided free land to settlers. To earn 160 free acres, settlers had to live on and farm the land for five years. This brought 75,000 people, mostly from Europe, to Minnesota within three years. The new homesteaders plowed the prairie soil and planted crops, creating many small family farms. Many of the first homes were built from prairie sod. Farm machinery like steel-blade plows, mowers, reapers, and harvesters were invented to help with the work.

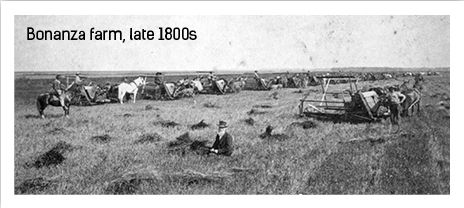

Bonanza Farms

Wheat production grew as new railroads connected farms to markets. Between 1875 and 1890, huge bonanza farms were created, especially in the Red River Valley. Funded by rich business people from eastern states, wheat farms covered thousands of acres. Hundreds of horses and huge teams of farmhands and machines worked these specialized farms (farms that grew mainly one crop). Most of the wheat was shipped to flour mills in Minneapolis.

Eventually, bonanza farms produced so much wheat that a surplus (oversupply) was created. Wheat was no longer profitable. Many bonanza farms were divided and sold, making smaller family farms again. Families began growing corn, oats, and a new hay crop called alfalfa. Some planted fruit trees. Others chose dairy farming, especially in the rolling countryside of southeastern Minnesota.

From earliest Native American farmers to arrivals from another continent—all were pioneers of Minnesota agriculture. Today, there are many kinds of farms in Minnesota, from family farms large and small, to large farms specializing in corn, soybeans, or sugarbeets, to cattle, sheep, poultry, and goat farms, to organic farms, to Native American wild rice sites-even farms raising llamas!